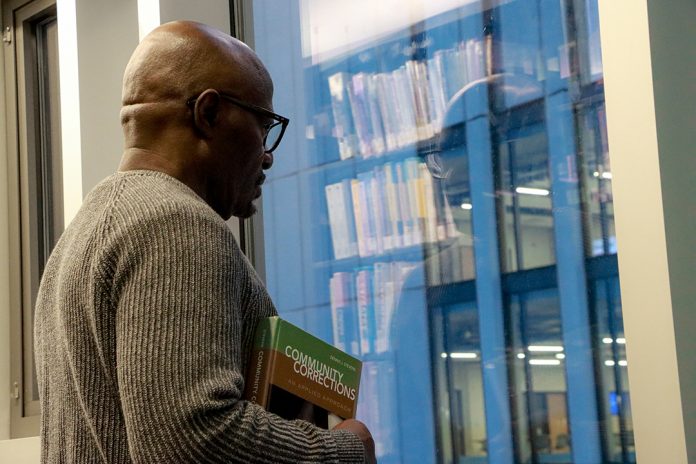

When Kent Larson’s phone rings in the afternoon, he knows what to expect before he even looks at the screen.

It’s usually one of the men he mentors through Celebrate Recovery, calling from a correctional facility to talk through whatever he’s facing that day.

Larson never rushes the conversations.

After nearly 40 years of sobriety, he understands how consistency can shift the course of someone’s life. What strikes him most is how many of the men he supports never had that stability to begin with.

“Some of the horrendous things that went on in their lives destroyed them,” he said. “It absolutely destroyed them.”

Those calls reveal a pattern he recognizes well: people rarely end up in the justice system because of one moment. Most often, the path starts much earlier, in the absence of community, resources, or belonging.

Poverty, unstable housing, and systemic inequities disproportionately affect Black and Indigenous youth, increasing the likelihood of early justice involvement. A 2025 report from McMaster University found long-standing disparities in who is detained in Ontario.

In 2021, Indigenous and Black males were detained at far higher rates than white Canadians with nearly 3 per cent of Indigenous men and 2 per cent of Black men in Ontario entering custody. Indigenous women faced the most severe gap, with detention rates 15 times higher than white women.

These disparities stand out given the population numbers with Indigenous people making up only about five per cent of Canada’s population, and Black Canadians four per cent, yet both groups remain significantly overrepresented in the carceral system.

Jasmyne Julien, founder of Revitaled Reintegration Services, says many individuals she works with end up in the system not because of inherent criminality, but due to survival needs, unsafe environments and a search for belonging.

“There are many: survival, poverty, lack of support at home, unaddressed trauma and unsafe environments. Sometimes it’s self-defence. Sometimes it’s seeking belonging outside the home,” Julien said.

Understanding the Roots of Criminal Involvement

Over-policing, systemic bias and historical trauma compound to push marginalized populations toward the justice system.

The Laidlaw Foundation, a Toronto-based youth advocacy organization that focuses on advancing equity and supporting young people through education, justice and community-led initiatives, found in its 2023 report that Black and Indigenous youth in Ontario’s child welfare system are significantly overrepresented in school-based police encounters.

Zero-tolerance policies and discriminatory suspensions have created minor conflicts, or acts of self-defence, which often escalate into criminal charges for Black students.

For Indigenous youth, these experiences sit on top of generations of trauma.

According to a 2025 framework from the Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres, called they learn, urban Indigenous youth often carry the weight of “ongoing cycles of harm” rooted in disrupted knowledge transmission, family displacement and colonial systems that attempted to sever cultural identity.

These legacies continue to shape how Indigenous youth experience education, community supports and belonging, emphasizing that learning environments must acknowledge trauma, connection to community and cultural identity to support Indigenous youth effectively.

Asennaienton Frank Horn, board member of Indigenous Sport & Wellness Ontario, says a child’s home environment and daily structure can shape whether they become vulnerable to negative influences.

“The odds are stacked against some kids from the start if they don’t have structure at home,” he said.

Through his work, life and volunteering, Horn has seen how sports and community programs give kids a sense of belonging and keep them engaged in positive spaces.

He says having somewhere to go, and people who care can make a real difference.

“Idle time can lead to other influences, and sometimes those can be the wrong ones,” Horn said.

Without protective factors like consistent caregiving, community connection or access to supportive programming, youth often turn to whatever or whoever fills the gap.

Breaking the Cycle Through Community Support

Revitaled Reintegration Services focuses on prevention and early intervention. The organization offers peer counselling, youth programming, advocacy, mentorship and creative justice education.

One example is the upcoming LawLantis game, a web-based simulation following Sheamus, an Afro-Indigenous youth navigating the justice system after being caught stealing.

Players make decisions for Sheamus, learn legal terminology, understand court processes and explore restorative justice principles.

“Education is critical. When people learn what supports exist, they are more likely to seek them,” Julien said.

Revitaled also runs storytelling programs such as Your Stories Matter, which empower students to share personal narratives and build confidence through comics. These programs integrate Afrocentric and Indigenous principles, perspectives often missing from traditional justice education.

Julien emphasizes that mentorship, creative engagement and connections with community resources are key to diverting youth from the system, and partnerships with groups such as Celebrate Recovery, Yonge Street Mission, the John Howard Society, CMHA, Durham Justice Services, Durham Family & Cultural Centre and Durham Regional Police help expand access to support services.

Employment, Reintegration, and the Human Side

For adults leaving correctional facilities, stable employment, housing and mental health supports are essential in reducing recidivism.

The John Howard Society’s 2025 report, Sentenced to Unemployment, shows only half of formerly incarcerated individuals secure employment 14 years after release with many earning no income at all.

Housing stability is also a major predictor of success. A 2025 study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that reducing homelessness by 65 per cent led to a nine per cent drop in recidivism in just one year.

Larson stresses that human connection and consistent mentorship can make a tangible difference. “Helping them also helped me. It’s incredibly meaningful work,” he said.

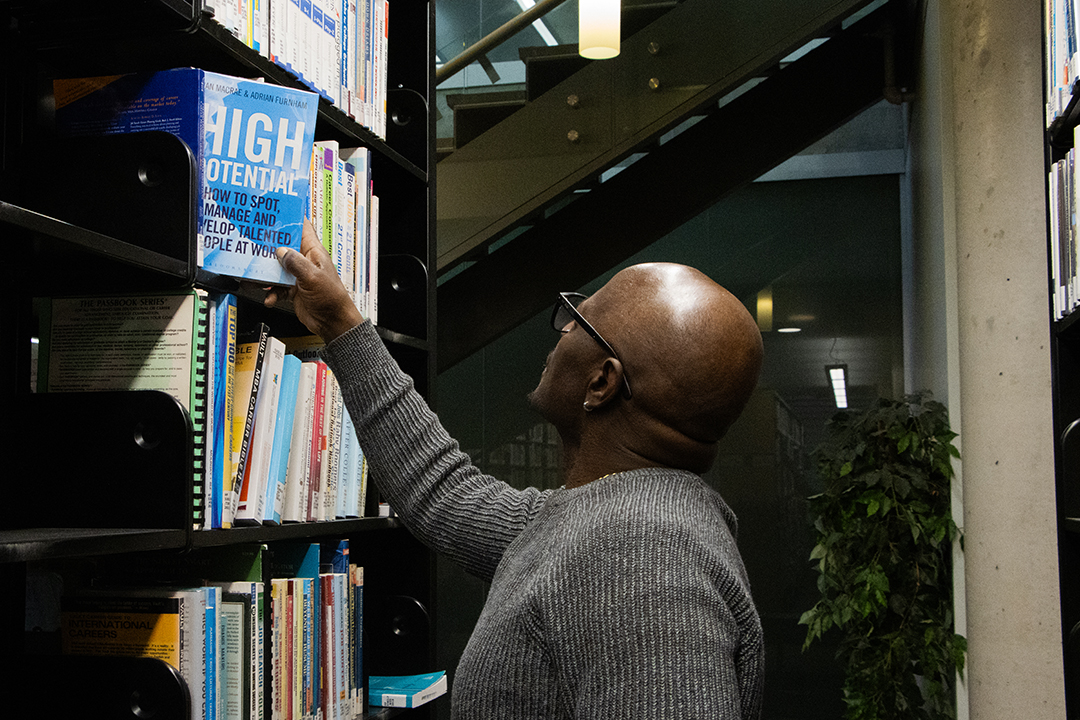

This is also where education-based programs like Walls to Bridges play a critical role.

Walls to Bridges brings university and college courses inside correctional facilities, allowing incarcerated individuals to learn alongside students from the outside.

These programs offer more than academic credit.

A 2025 report by the University of Toronto and Wilfrid Laurier University, found that postsecondary classes inside prisons help challenge the stigma of the “uneducated prisoner” and open space for self-expression, confidence-building and transformation among participants.

Their study emphasizes that correctional education humanizes incarcerated students and fosters learning environments where people can reconnect with their strengths, a key part of preparing for life after release.

Julien says success often looks like stabilization: finding work, secure housing, accessing mental health services or connecting with consistent supports. For youth, it often means gaining confidence and a voice through storytelling initiatives and mentorship.

Larson still sees the impact of these connections firsthand. He hears regularly from one man he has supported for years. Despite never meeting in person, their weekly phone calls have become one of the few constants in a life shaped by instability.

“He calls me every week to talk,” Larson said. “Apparently, he’s going to be coming out shortly. I’ve got to deal with that when the time comes.”

Larson worries about what waits for the man outside: whether housing will be available, supports will remain consistent, and whether he will find the sense of belonging he has never had.

Reintegration is fragile.

Missed services, unstable environments and further isolation can undo months of progress. But connection, consistency and support can help.

Sometimes one steady voice on the other end of a phone is enough to keep someone grounded.