Content Warning: This story discusses suicide, PTSD and mental health struggles among first responders. If you or someone you know is struggling, help is available.

According to the National Library of Medicine, suicide rates among first responders are significantly higher than those of the general population. Between 2014 and 2018, firefighters had a suicide rate of 5.8 per 100,000, while paramedics faced an even higher rate of 7.3 per 100,000.

“I have had friends of mine who have been in the service who have actually committed suicide from (post-traumatic stress disorder) PTSD-related illnesses,” said Tony Watson, an instructor at Durham College and a captain with Vaughan Fire Rescue Service.

Additionally, Public Safety Canada estimates that between 20 and 45 per cent of public safety officers struggle with PTSD or another mental health condition.

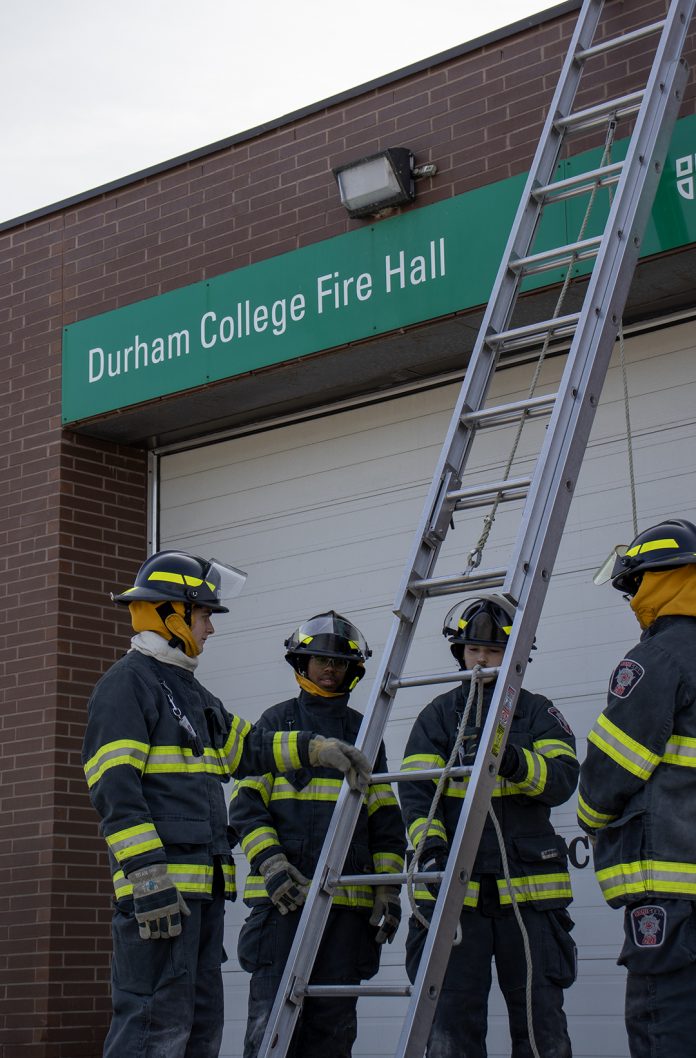

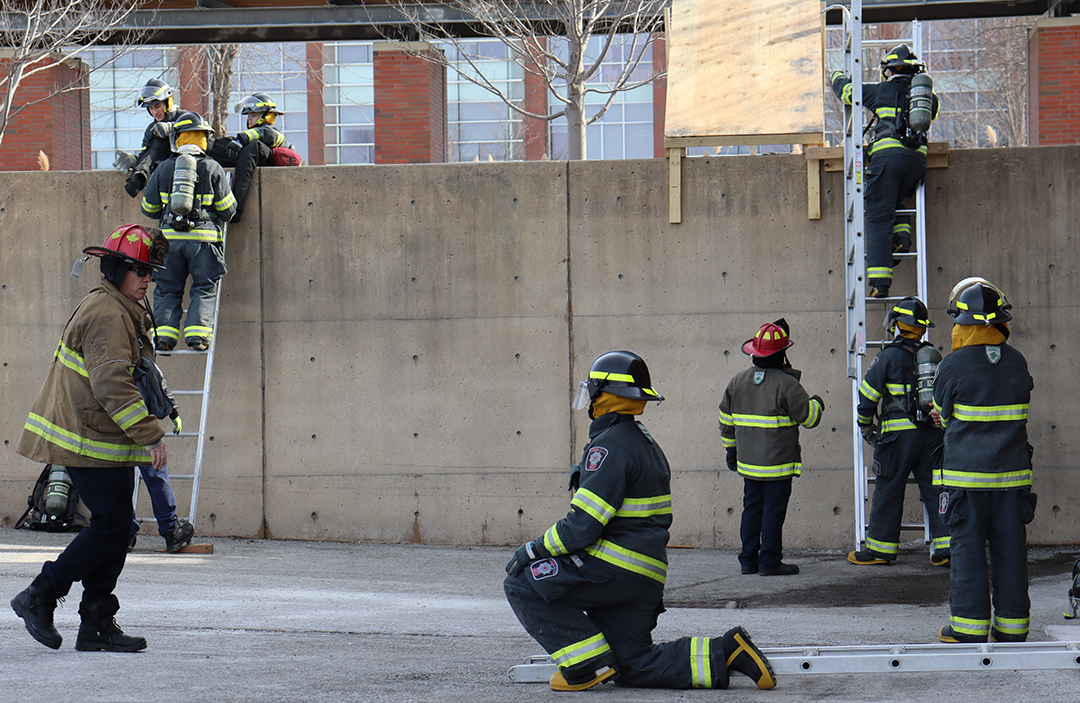

At Durham College, first responder educators and students are working to break the stigma surrounding mental health in emergency services. Their goal is to equip future professionals with the resilience needed to navigate their careers.

Watson, who has more than 15 years of experience as a paramedic and 28 years in the fire service, understands the psychological weight first responders carry.

“Every call comes with different challenges,” he said. “One day, it’s a house fire. The next, it’s a medical emergency or an auto extrication. We’re constantly faced with high-pressure situations where the public relies on us.”

To address these challenges, Durham College has incorporated mental health-related courses into its pre-service firefighter, police foundations, paramedic and protection, security and investigations programs.

These courses help students focus on self-care, recognize signs of mental health struggles in themselves and others and connect with appropriate support resources.

Fitness coordinator Glen Barkley also provides Warrior21 training, a 21-day program focused on resilience and mental health, to pre-service firefighters.

The goal is to prepare students for both the physical and psychological demands of the job.

Jeff Robbins, an instructor in Durham College’s advanced and primary care paramedic programs and an active paramedic, has seen a cultural shift over the years.

“When I started my career, the mentality was, ‘Suck it up and get back to work,'” he said. “You were expected to go to the hospital, drop off your dead baby and immediately go back out. There was no such thing as taking a break or time off. That’s changing now.”

Robbins acknowledged the progress made in recent years.

“I would say that the stigma surrounding seeking help is slowly disappearing from the industry,” he said. “The services are recognizing that you need downtime after stressful calls. And with the turnover of paramedics, we’re changing the culture slowly.”

Many services now recognize the need for decompression after traumatic calls. Watson said his fire department pulls firefighters out of service for three hours after a critical event.

“During this time, they can grab a coffee, go to the mall, take a little bit of time, or they can go back to the hall and decompress on their own,” he said. “They’re out of service, except for structure fires.”

He emphasized the importance of situational awareness and recognizing key signs and symptoms. His department also has training in place for recruits to understand their own signs and symptoms, as well as what to look out for in others.

“We also include their spouses; they participate in this program as well,” he said. “So they are able to point out signs too. When you’re in the position, you may not recognize them all … having your spouse involved makes a big difference.”

At Durham College, courses also cover topics such as recognizing burnout, understanding critical incidents and identifying mental health struggles.

Dale Button, an instructor in Durham College’s advanced and primary care paramedic programs, said students are encouraged to connect with a psychologist, counsellor, or therapist to manage daily stress and seek support during tough times.

“We’re just normal people and we have our own trauma from life,” Button said. “If I’m not managing that really well … adding a huge external stressor can be hard.”

While formal mental health programs are essential, first responders often find the strongest support among their peers. Before students enter the field, the program trains them to be peer supporters.

“Say I do a call that’s not sitting well with me, I can call one of those peer supporters who is in my program, in my cohort and I can talk to someone I feel more comfortable with,” Button explained. “They’ve been trained to provide feedback, a little bit of feedback and direction.”

He acknowledged that “I think it has been one of the biggest benefits for us,” as the program sees 30 to 40 contacts per month. The same is true for pre-service firefighting training.

“There’s a special bond among first responders,” Watson emphasized. “We walk through the trenches. With our peers, we’re able to have those conversations and that stigma is finally starting to move away. That communication line is now being bridged.”

Robbins echoed this sentiment, stressing the importance of open communication between instructors and students.

“We try to let our students know from day one that it’s OK to not be OK. It’s OK to seek out help,” he said.

For students like Sophia McQuay, a 20-year-old in Durham College’s pre-service firefighting program, mental health awareness is critical.

McQuay, who has borderline personality disorder (BPD), credits the program’s openness and support for helping her develop healthier coping mechanisms.

“I haven’t gone to any of the guidance or social workers here because I don’t find it necessary because our instructors are so open and willing to talk about things,” she said. “They’ve been through so much and I really do look up to them.”

She added, “Not just because they’re physically successful in their careers, but because they cope with what they deal with every day in such incredible ways.”

She highlighted programs like Warrior21, which focus on mindfulness, breathing exercises and gratitude practices to help students prepare for the challenges of the job.

“You grow a little family in here, and you’re all very close … These are my people now,” McQuay added.

McQuay, who also works for the mental health brand War Within, advised those entering the field to seek therapy early.

“Look for a therapist now so that we can develop a rapport and develop a relationship before we start talking about the difficult things we will be enduring during our time on a force,” she said.

Despite the progress made, there is still work to be done. Button, who has been a paramedic for more than 15 years, understands the toll the job can take.

“That is probably the million-dollar question: how to prepare people better for a job that is so challenging,” he said. “This is not a normal job. These students will see things that a very small percentage of the population will ever see once, let alone hundreds of times.”

Button acknowledged that in the past five years, society has become more progressive in recognizing mental health as a crucial aspect of well-being. The stigma around it has started to fade.

“We try to model good behaviours, so almost all of our faculty and facilitators are active-duty paramedics,” he explained. “I’m very open with my students when I do a call or experience something that doesn’t sit well with me and what I’m using to feel better.”

By sharing their own experiences, instructors help normalize discussions around mental health.

“We can’t beat students down and then expect them to perform well on the road. We have to foster a positive environment in their education, just like we do in the field,” Button said.

Reflecting on his career, Button recalled a difficult call.

“I attended a car accident with multiple patients. There were four or five dead people on the scene. It didn’t sit well with me. I remember thinking, ‘Something’s not right. I don’t feel OK,'” he said.

After days of feeling off, he turned to his psychotherapist for support.

“The important piece was not letting it linger. I needed to talk about it immediately, not let it fester for months or years,” Button added.

He admits that his own paramedic training didn’t prepare him for this aspect of the job.

“My training didn’t help me and I don’t think additional training would have helped. What mattered was recognizing my symptoms and seeking professional help.”

For those considering a career in paramedicine, Button offers three key recommendations: What does help look like for you? What does your support system look like? And what is the relationship you have with a mental health professional?

“These are humans responding to trauma just like anyone else would day to day,” Button said. “That’s what makes the job so challenging: there’s no magic solution to dealing with the type of trauma that you experience as a paramedic. It is having robust support systems in place to manage it.”

Students at Durham College can access free mental health supports through the Campus Health and Wellness Centre, including counselling, wellness coaching and 24/7 help via the I.M. Well app. For details, visit durhamcollege.ca/wellness or call 905-721-2000.