Jackson Park in Peterborough is known as an oasis in the city, by the city. Designed between 1894 and 1895 by local architect John Belcher the park is 1.8 hectares (45 acres) and is known as being the “Central Park” of the town.

The park is located on the traditional territory of Michi Saagiig and Chippewa Nations. Jackson Park is home to many plants and trees that are significant for Indigenous cultures. Cedar is one of the four sacred medicines and native to the park.

According to Doors Open Peterborough’s self-guided tour of the park, Cattails, mint, spruce and birch also grow in the park, and each represents an element of “holistic world view that emphasizes the interconnectedness of all living things on Earth.”

In the past, the park was home to movie nights, concerts, tobogganing and skating. In 1904, the Peterborough Radical Railway Company made its first trip through Jackson Park.

The park also quickly became a gathering place for community events. In December of that year, hundreds of lights were covered with Chinese Lanterns for a special launch called, “open air rink.” Passengers on the streetcar could step right off the trolley and onto the ice rink or head up a hill for toboggan runs.

Ten years after the first streetcar ride in the park, the Radical Railway Company sold its operations to Ontario Power Generation after experiencing financial trouble. By 1926, the streetcars stopped running in the city and were replaced with busses.

Belcher used many techniques from Victorian architecture and inspirations from Japanese gardens to instill a more romantic and foreign feeling and esthetic to the park. The site has served as the backdrop for many weddings in the warmer seasons and countless family events.

The park itself was awarded a Heritage Designation on Dec. 6, 2021, but one attraction in the park earned this title decades earlier.

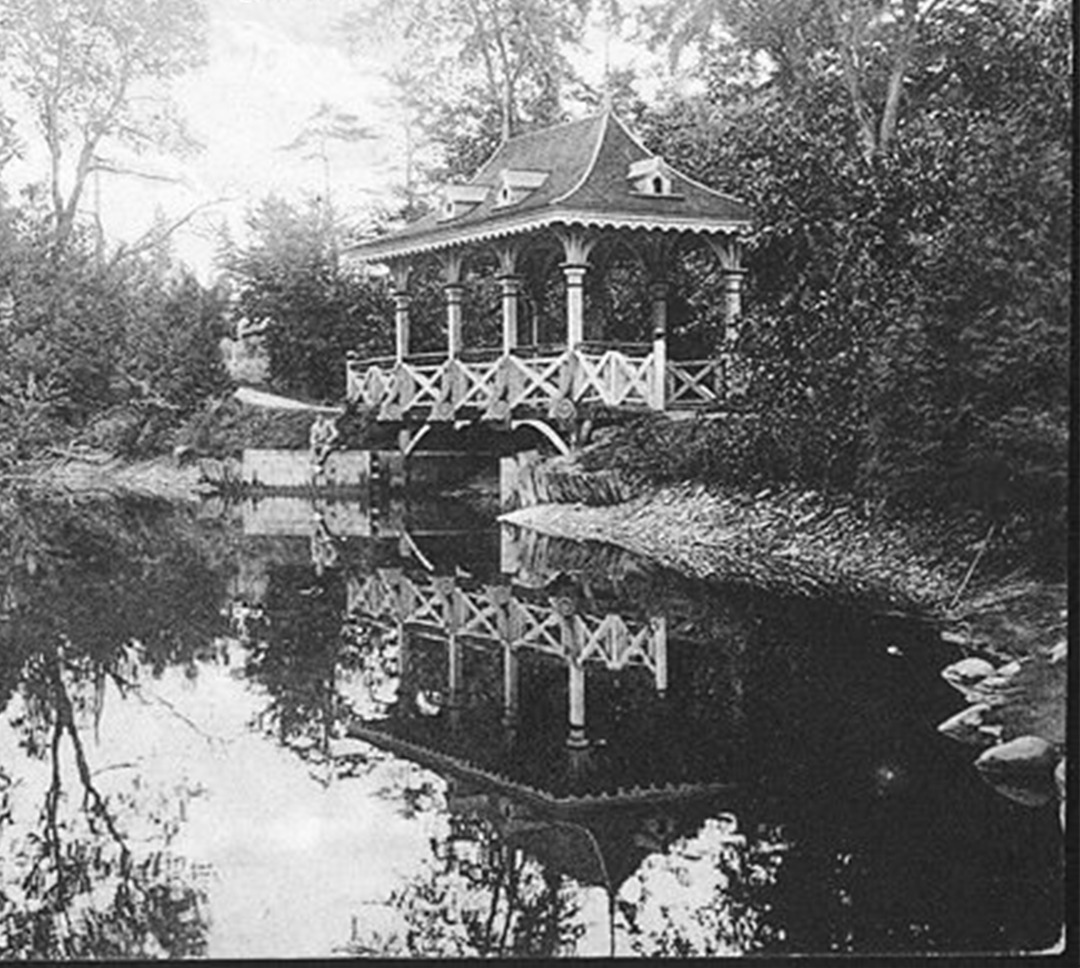

In 1981, the Pagoda bridge was designated under the Ontario Heritage Act by the City of Peterborough. This is one of three main sights in Jackson Park and for some it is seen as the heart of the park itself.

The bridge is made of wood and covered with gothic and romantic detail. It runs over a creek of approximately six metres of water, and takes after the Victorian era with its brackets, trim and the curved hipped roof. The roof is designed with six small dormers that act as bird houses.

In the 1960s the City of Peterborough took over responsibility for the bridge, and it soon started its decline.

Ann Farquharson grew up living close to the park. Her mother Elizabeth Farquharson was chair of the Parks and Recreational Board and Jackson Park played a key role in their lives.

“I remember playing around the area, and really enjoying it. It was kind of an extended playground,” Farquharson said.

When her mother became aware of the state of the decaying bridge “she sprang into action,” Farquharson said.

Not only was Elizabeth the only member interested in the park, but also the only woman on the board. She created the “Preserve the Pagoda Bridge” committee, and they were able to raise $30,000 dollars to restore the bridge.

Elizabeth was involved in many activities and projects that would make Peterborough a better place, including the Hutchison House project. This was the home of the first doctor in Peterborough. Built in 1837, the home has been restored to its former glory. For her efforts, Elizabeth was named “Citizen of the Year” in 1989.

“I am thankful that she accomplished so much. I am very proud of both of my parents,” Farquharson said.

She has continued the legacy that her mother started. To honour her parents, she has placed two benches next to the Pagoda Bridge. One for her father, Gordon, who she describes as “a spitfire pilot, and a lawyer who actually met Winston Churchill.”

After the passing of her father Gordon in 2004, she sponsored a bench inscribed with the Churchill quote, “A nation that forgets its past has no future.”

“I put that on there, and then when my mom passed away, I was hoping to encourage more people to put benches up in the park. And it’s worked,” Farquharson said.

Today, the park is home to many commemorative benches and plaques honouring past community members, like Farquharson’s parents.

When the bridge was saved, and the park was deemed a historic landmark, there was a big celebration. Dignitaries, community members, families and kids all came together to honour the park. People wore historic outfits, and there were potato sack races.

“It was such a wonderful celebration because it was such an important historical site,” Farquharson said.

Jackson Park has continued its legacy as a space for the public. It’s somewhere the community can gather and get a sense of nature and history, even before the nineteenth century. During these times, in the U.K., many cities had private parks only accessible to the wealthy. Everyone was, and still is, able to appreciate Jackson Park.

“Any town would die for a natural park like that in the middle of their town. It’s our Central Park. It really needs to be cherished,” Farquharson said.

Although the park is trusted in the care of the city, she believes there is still more to be done.

“The pond needs work. The number one priority right now, other than a coat of paint on the Pagoda Bridge, is the Caretaker’s Cottage,” she added.

The cottage was built in the late 1910s and follows a more rustic style with cobbled stone foundations and a chimney. There are big iron gates blocking the cottage from the road which were rebuilt in the 1960s. After talks of tearing it down in 2023, the city has decided not to demolish it.

“How could anyone even think to recommend tearing something like that down?” Farquharson said.

With the park and all of its elements being so important to the community, it’s a way for people to look at the history of Peterborough, she added.

“People need to care about (historic sites),” she said. “That’s part of the problem, too, not having ties to the community, and not realizing the importance of landmarks.”