When Saroya Tinker’s white mother was at one of her daughter’s games, she was asked by a parent from the other team who her daughter was.

“My mom said number 71 and you could tell that I’m Black while I’m on the ice,” says Tinker. “The parent from the other team said, ‘Oh wow, that’s awesome like, crossbreeds always make pretty good athletes,’ and my mom was like I’m sorry, what? She’s not like a horse or a dog or something …”

Tinker was drafted into the National Women’s Hockey League (NWHL) in April 2020 and currently plays for the Metropolitan Riveters in Calgary Alta. She continues to deal with microaggressions and was blatantly called the N word by a teammate.

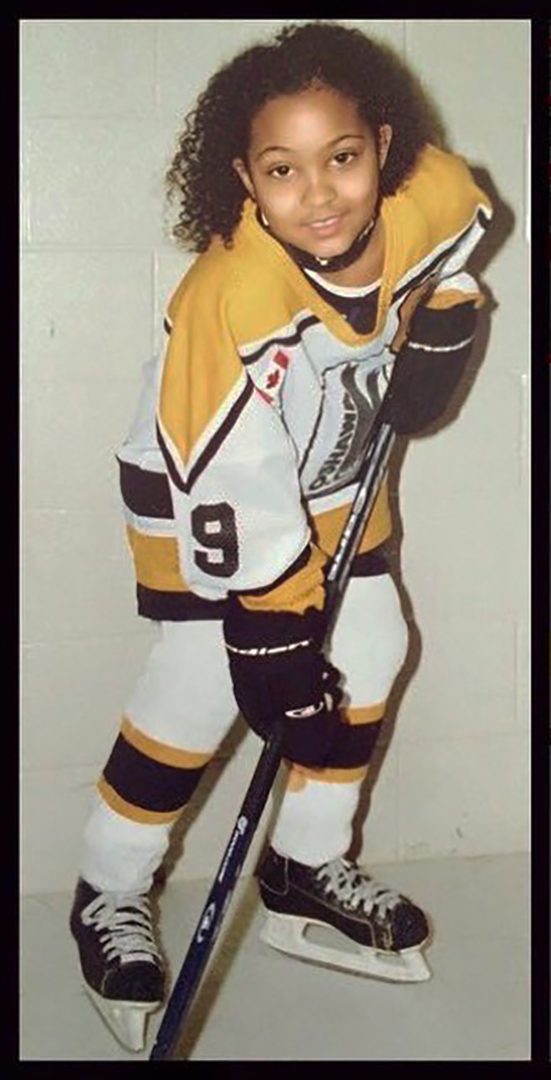

From a young age, Tinker grew up in Oshawa and when she started playing hockey was the only girl on her team for the first three years.

“It was different being a girl playing and I think at that point, I didn’t really realize how the colour of my skin was going to affect me in the game as well,” says Tinker.

Tinker didn’t have many Black women hockey players as influences, except for Angela James.

“Her last Olympic year was 1998 and she was the only Black girl that played hockey at that point,” says Tinker. “1998 was the year I was born, and she had already retired.”

Hockey is Canada’s national sport, but it barely reflects its people and is one of the least diverse sports when it comes to Black, Indigenous or people of colour (BIPOC) playing professionally, on the college level or just hockey in general.

Donnovan Bennett is a writer at SportsNet and has been writing in sports for 15 years. His passion for football and basketball inspired his career, but it grew, he wanted to focus on good storytelling, no matter what sport, including hockey.

“We consider ourselves in Canada to be a progressive and diverse country, and progressive and diverse are two words that you wouldn’t use to describe hockey, historically,” says Bennett. “If hockey is our game and our love and our passion, it should fall in line with the values that we have as a country.”

According to WSB-TV Atlanta in 2011, close to 93 per cent of the league’s players were white with only 32 who were Black or other ethnicities.

In 2020, 43 players for the NHL were of colour and three of them played on one team – the Red Wings, according to Wayne State University’s WDET 101.0 FM.

Today, Tinker is one of four Black women playing in the NWHL, with each playing for a different team in the league, except for Connecticut’s team.

“I think that it’s just another level when they can see somebody who looks like them and want to participate in it,” says Tinker.

As a Black sports journalist, Bennett says it’s great to see more women of colour on the ice now than ever before.

“I love that these women are saying I’m going to be great at a sport that isn’t traditionally one that I’ve found space in,” says Bennett. “I think the commonality, other than their skin colour, is that they are great, like there is certainly Black girl magic going on when you look at Black females and hockey.”

Bennett says he hopes to see many young Black girls look up to professional hockey players, not just to follow in their footsteps but to see them as role models because they persevered when odds were against them.

Tinker wished she had more mentors and girls to look up to when she was younger, but her goal is to be a role model to young girls of colour who want to play hockey.

“The main thing that keeps me going and keeps me wanting to play is just the younger players of colour who are coming up behind me,” says Tinker. “It’s so important in their careers that they have a role model, so that’s definitely what helps me continue playing.”

In 2018, the idea of empowering young Black women who love hockey, Black hockey voices, and allies turned into the Black Girl Hockey Club (BGHC), founded by Renee Hess, an Associate Director of Service Learning at La Sierra University and Pittsburgh Penguins fan.

BGHC looks to educate the hockey community on anti-racism initiatives with web seminars and panels. The club also provides scholarships, three times a year for Black girls between the ages of 9 and 18 to have accessibility to play.

Makayla Sheppard, winner of BGHC’s scholarship for fall 2020, says she is aware hockey is predominantly a white male sport, but seeing how diverse it is becoming gives her hope.

“Hockey is a very expensive sport, and all the support she has received from BGHC has been beneficial,” says Amanda Sheppard, Makayla’s mom. “She sees that there are many other females just like her through BGHC, and it motivates her to keep playing and be the best player and person she can be.”

Sheppard says none of Makayla’s school friends play hockey, and are amazed at what she can do on the ice. “Also, being a young woman of colour, it allows Makayla to be a role model for younger girls entering the sport and having someone to look up to,” says Sheppard.

The club’s ‘Get Uncomfortable Campaign’ was designed to stop racism in hockey on and off the ice.

It was created in August 2020 and took eight weeks to come up with the pledge, according to Sebastian Jackson who joined BGHC just before starting the campaign.

“We just wanted to create a pledge and make a difference and try and take a big step forward in making hockey more inclusive,” says Jackson. The Google Form takes five minutes to complete and asks those who sign the pledge to commit to disrupt racism on and off the ice and make hockey welcoming for everyone.

“It’s the perfect first step to admitting that hockey has a problem,” says Jackson.

Prior to joining BGHC, Jackson was vocal about issues surrounding hockey and coloured communities. “My focus now is strictly on inclusivity and trying to make this game better,” says Jackson.

Jackson has been involved in hockey for 20 years as a scout, a vice president and a general manager for junior hockey teams.

“I always wanted to turn it into a career but being a colour person, you do have to work twice as hard to get the same amount of opportunities as a white person with the same qualifications,” explains Jackson.

Jackson has also experienced times where he was the only Black person throughout his ten years of playing the game or being in a room as the only person of colour.

“Most times I’ve walked into an area and seen less than a handful of Black or coloured people usually,” says Jackson. “You start to look around, and you’re like, I’m alone in this, and some people don’t see it that way.”

Although Tinker and Jackson loved the sport from a very young age, they noticed how each of their parents spent thousands of dollars and how inaccessible equipment is for many communities, which decreases the interest of BIPOC players in hockey altogether.

“The highest that I ever played was about four grand, but there are teams charging about 15,” says Jackson.

“I think more advocacy and push for BIPOC players to be in the sport will start to increase accessibility,” says Tinker. “With more BIPOC players being there that means more mentorship and more equipment being donated.”

In the meantime, Tinker wants to continue to be the face for young Black girls who love the game of hockey.

“When I see little girls wearing my Tinker jersey, that their dad bought… it shows that you are affecting them,” says Tinker. “They can be whatever they want to be, there is representation and there are people up at the top that are rooting for them, wanting them to make it there with us.”