When Sol Mamakwa, MPP for Kiiwetinoong, rose at Queen’s Park on May 21, 2024, he began speaking in Anishininiimowin, or Oji-Cree, an Indigenous language.

His 10-minute speech was the first time that anyone had spoken any language besides English or French in the Ontario legislature, and the first time it was interpreted and transcribed.

The New Democrat urged Indigenous people to revitalize their languages and called for other legislative bodies to allow Indigenous languages to be spoken officially.

He said, “I’m very grateful… thankful for the opportunity to be able to speak my Anishininiimowin, Indigenous Oji-Cree language in this legislature,” through an interpreter.

Mamakwa also answered questions in his native language. He dedicated this speech to his mom, Kezia Mamakwa, who turned 79 years old on the same day and taught him Anishininiimowin.

According to the Assembly of First Nations, there are over 60 unique Indigenous language dialects spoken in Canada, and all are considered critically endangered, except Inuktitut.

The loss of Indigenous languages is a global issue.

Of the roughly 6,700 languages spoken in the world today, 96 per cent are spoken by three per cent of the world’s population.

For generations, deliberate policies such as residential schools and church-run day schools worked to sever Indigenous children from their languages, cultures and families.

The effects have been devastating and long-term.

For DC alumnus Toby VanWeston, the path back to language is personal. Raised in a Cree-speaking household on the reserve, he was once able to understand everything his grandmother told him. As he grew older, English took over.

“I used to be fluent in understanding,” he said. “Then it was just gone. I’d hear the language and only catch pieces.”

According to the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, only about one in eight Indigenous people reported being able to speak an Indigenous language well enough to hold a conversation.

But rebuilding is no simple matter. Many surviving fluent speakers are Elders, and many languages were never codified in writing.

Today, VanWeston is learning again slowly, using a Cree language book, “mâci-nêhiyawêwin / Beginning Cree” by Soloman Ratt, and learning pronunciation from his mother who is fluent.

Oral transmission, once the heartbeat of Indigenous wisdom, has been disrupted. Once a speaker passes, the nuances of dialect, pronunciation and stories may vanish forever.

The share of Indigenous people who learned an Indigenous language as their mother tongue continues to decline.

In 2021, there were 184,170 people with an Indigenous mother tongue, a drop of 7.1 per cent from 2016, reflecting the ongoing erosion of intergenerational transmission.

Jacob Powless, another DC graduate, said he learned a little bit of Mohawk from his dad.

“For me, growing up, Shé:kon, skennenkó, that was stuff my dad used to say to me every morning,” he said. “That just drilled into my brain.”

Powless said that anti-Indigenous racism still exists and bigotry still makes people hesitate learning and speaking their Indigenous language.

“Do you remember what we did in Oshawa last year for Indigenous People’s History Month? Nothing,” he said that is how racism continues to present itself in the city.

MPP Mamakwa is the provincial critic for Indigenous and Treaty Relations, and scrutinizes government First Nations, Métis and Inuit policy, advocating for Indigenous rights, self-governance and reconciliation.

In this role, Mamakwa can push for nation-to-nation respect, land stewardship, cultural protection and equitable resource sharing, to honour distinct treaty promises and inherent rights.

Julie Pigeon, an Education Advisor with the Mississaugas of Scugog Island, said the issue with language is nuanced, but it begins with a lack of teachers. She said the funding is essential.

“What has consistently happened over time is that those have that knowledge are undervalued within the regular education system,” said Pigeon. “So if you are a teacher who’s not OCT (Ontario Certified Teacher) qualified, and you are able to teach the language, they would pay you like at minimum wage.”

Language revival requires sustained commitment and funding.

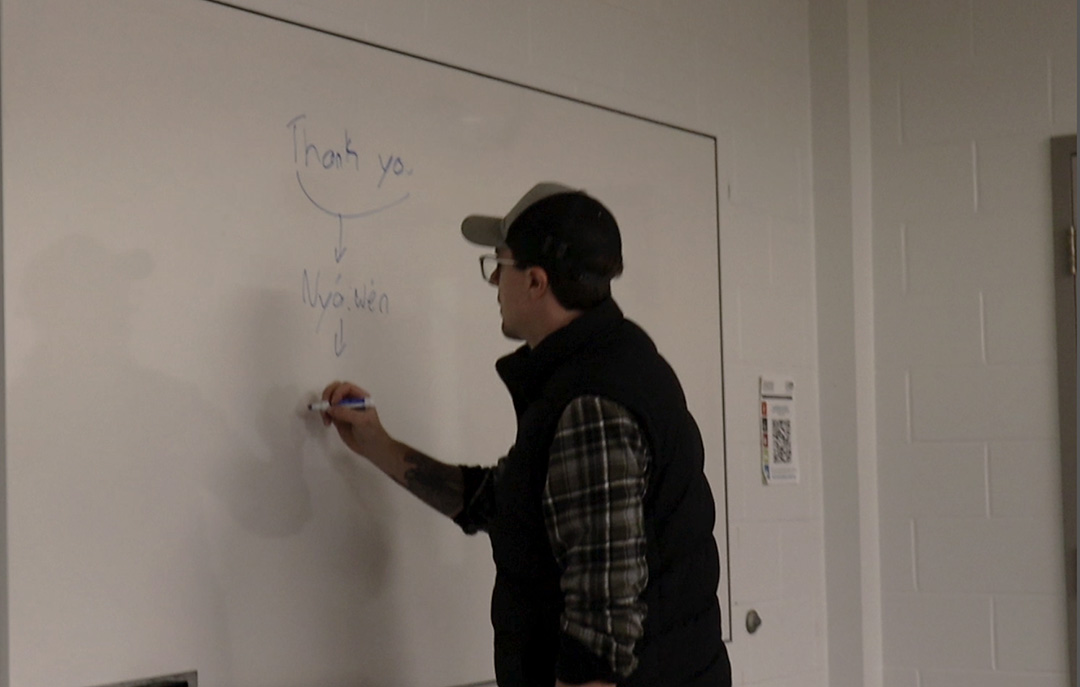

At Durham College (DC), language classes through the First Peoples Indigenous Centre (FPIC) are made possible through a partnership with the Durham Community Health Centre.

Rachel Taunton, the Indigenous Communities Outreach Coordinator at the FPIC, describes the centre’s role as creating culturally safe spaces where learners aren’t judged, and where traditional knowledge can be passed forward.

“For many students, this is about reclaiming identity,” Taunton said. “Our purpose is to allow a space for students to find the sense of community they may have left behind on their post-secondary journey.”

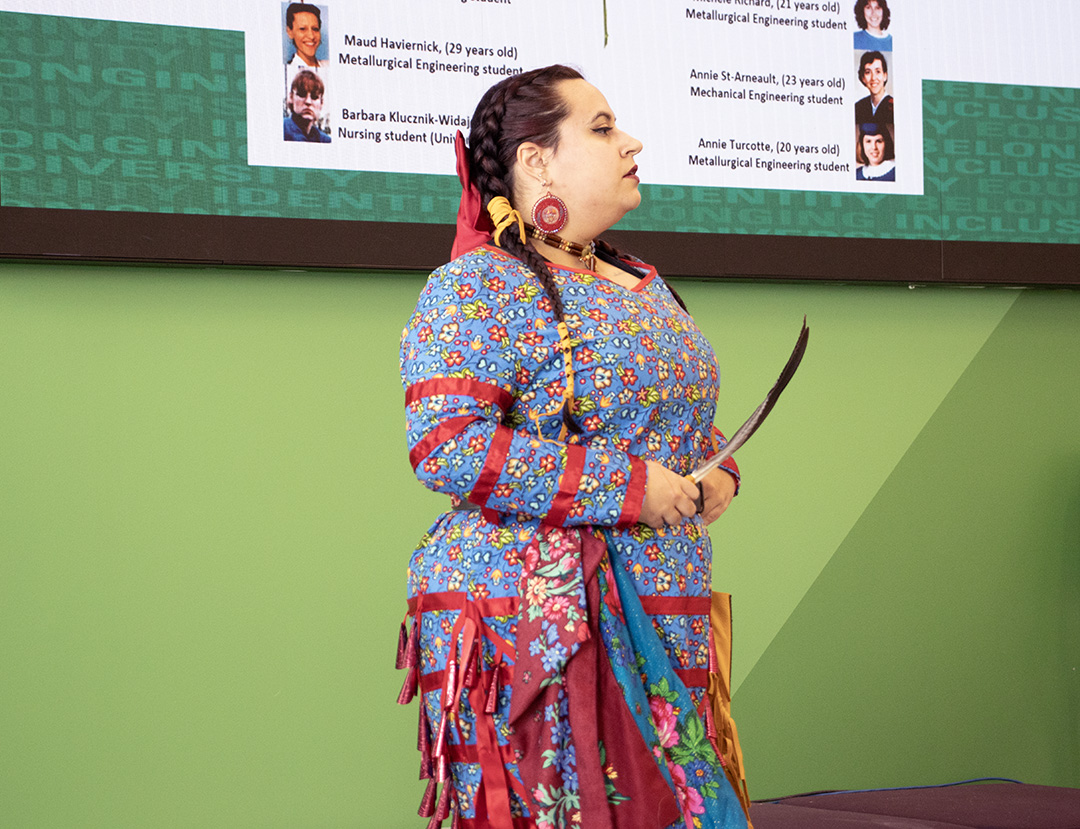

The FPIC offers monthly language classes; in December, it was led by Showna Smoke, a language keeper from Alderville First Nation.

Learning a new language is hard. Without enough teachers, people similar to Powless who live in urban areas, off-reserve, struggle to connect to language in person to expand their knowledge.

Powless said he uses an app on his phone to continue his learning, while his brother takes language classes at Tyendinaga.

Smoke learned Anishinabemowin by taking language classes as a child and even more at Trent University, where she took Indigenous Studies. Despite this, she says she will never be fluent; she is a lifelong learner.

She said teaching and learning the language was never a question; it was a passion and responsibility. She believes that language revitalization is important for reconciliation and healing for the affected communities.

For many, learning the language is more than words; it is reclaiming memory, connection and identity.

Ontarians were reminded that “official” language doesn’t just mean English or French, at that moment in May of last year at Queen’s Park.

It also must stand symbolically for the first language of this land. Revitalization efforts are essential to reconciliation, and this is how Indigenous peoples can express their truth.

“I am speaking for those that couldn’t use our language and also for those people from Kiiwetinoong, not only those from Kiiwetinoong, but for every Indigenous person in Ontario,” said Mamakwa.

The message is simple: language loss was intentional. Revival must be intentional, too.