A loud ringing echoes about the empty room, ricocheting off stacks of cardboard boxes.

Christine Chapman answers the phone with one hand and counts black centre pins for poppies with the other.

As the chair for the Royal Canadian Legion poppy campaign in Bowmanville, Chapman volunteers from the beginning of October to Nov. 11, expecting nothing in return.

“A lot of money is donated to the hospitals, veteran groups, the sea cadets, the air cadets, that’s where our money goes,” said Chapman holding tight to her large binder. “It goes back into the community. The Legion does not get a penny.”

It also raises money to support veterans and their families—covering everything from food to essential home repairs.

Due to a decline in membership and financial strain in recent years, several branches across Canada have closed their doors for good. This loss has lasting impacts on veterans and the communities that support them.

The end of the First World War

When the First World War ended, Canadian soldiers returned home in need of support. They quickly realized the only people they could rely on were each other.

In 1925, groups of veterans united to form the Canadian Legion of the British Empire Service League. In the early 60s, “British Empire” was dropped, and Queen Elizabeth II allowed the Legion to use the title “Royal.”

The following decades saw growth through remembrance education and youth community programs.

Today, the organization has 270,000 members across 1,350 branches, according to the Royal Canadian Legion website.

The oath

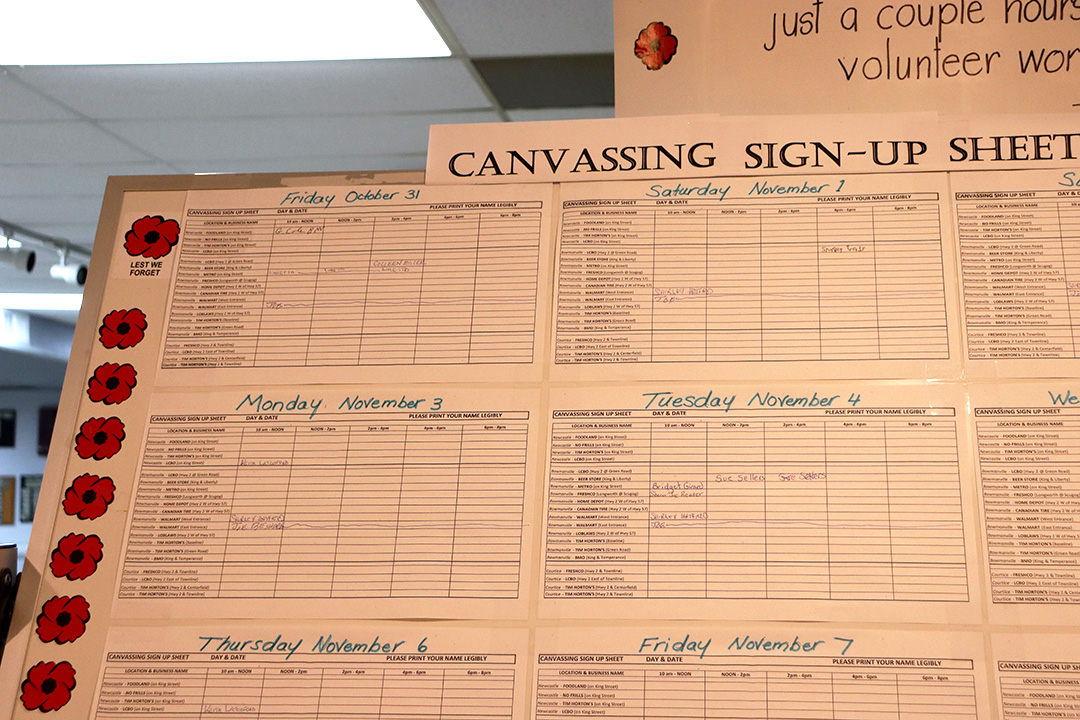

When they join, members swear an oath to support the poppy campaign. A promise that goes largely unfulfilled at the Bowmanville legion.

“We have a board out there that has numerous spots for people to donate two hours of their time, and we can’t get more than a dozen people,” said Rory Thompson, the legion’s property chair.

“It’s very important for people to remember the sacrifices that these people made. That’s why we’ve got what we have today because of what they did, and we better never forget about it,” said Thompson.

With an aging membership, the act of remembering becomes more difficult every year. As veterans die they take their stories with them.

According to a story in the Canada’s National Observer, about half of the legion’s members are aged 65 or older.

As the poppy chair, Chapman feels the effects of the aging demographic.

“They have physical ailments, or they’re just tired. You know they’ve put in 15 years, and they feel it’s time for someone else,” said Chapman.

The next generation

Larry Bryan, an active member of the legion and self-taught historian, has dedicated his life to sharing the stories of Canada’s veterans.

With his actions, Bryan hopes to pass the torch to the next generation.

“We don’t glorify war. They have to realize that everybody who ever signed the dotted line, myself and my brother, it’s a blank cheque,” said Bryan. “We signed our life to our country.”