The Ontario government recently invested more than $2-million in Indigenous mental health and addiction services in northern Ontario – an investment that’s raising questions locally about how those kinds of programs should be run.

Wellness programs in communities that receive government funding often face stringent deadlines and rules.

“We always have to adhere to these dates that the government sets and so we’re telling our community members to ‘Hurry up, you need to heal by March 31st,'” said Kristen Tranche, the regional health and wellness director of the Dehcho First Nations.

She says this insistence on healing in a certain way pressures these communities to make their programs fit the government’s vision instead of supporting what people want to see in their communities.

Some believe awareness is another barrier because people don’t know how to find resources in communities with “culturally appropriate” programs.

“I would definitely say a lot of Indigenous people like myself don’t exactly know where to go or how to access these resources…I personally don’t need to use them, but I feel people in my community may need to,” said Olivia Copeland, a Durham College Animation student who identifies as a member of the Chippewas of Rama First Nation.

To combat this, some reserves, such as the Chippewas of Rama First Nation, have started sending surveys to their community members.

They ask if people are aware of and know how to access wellness services in their area.

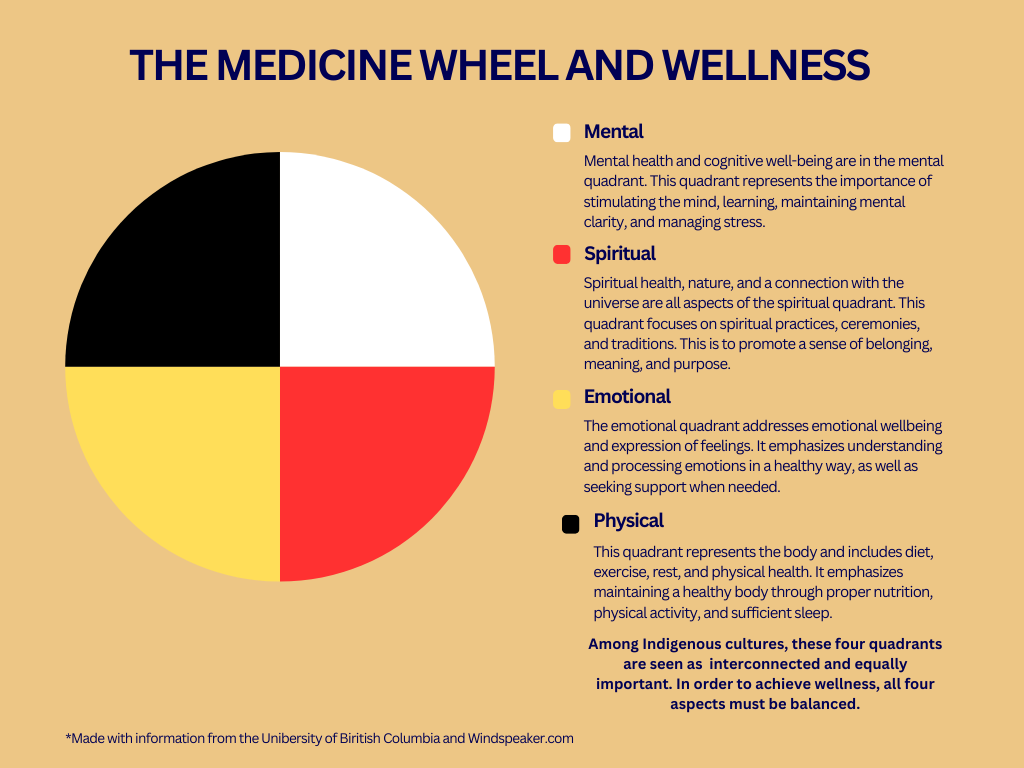

Some communities approach wellness from more holistic, medicine-circle-based perspectives, focusing on four main parts of a person, contrasting with other approaches focusing on the mind.

This approach works with the physical body, emotions, intellect, and spirit to ensure each component remains healthy and balanced to achieve wellness.

“Culturally appropriate care” goes beyond having professionals who are trained in addressing the complex traumas of these communities.

“Care is based in culture, whether it’s Western culture or Indigenous culture and every culture has a set of expectations about how care will be provided and what wellness means,” said David Newhouse, a Trent University professor who identifies as Onondaga from the Six Nations of the Grand River community.

“When we talk about Indigenous culture, the appropriate care, what we’re talking about is a series of actions that are grounded in Indigenous understanding of care and Indigenous understanding of wellness.”

Copeland says this is something that is needed.

“I feel that mental health is always overlooked by the older generations versus our generation,” she says. “It is an important thing that people struggle with in silence all the time.”

Some say the key is communicating openly and listening to Indigenous communities.

However, others say Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities can help by educating themselves and opening up dialogues about change.

“It doesn’t matter where we start, the important thing is that we start. So we look at those four directions and say, okay, where can I make a difference,” said Newhouse.

“So it doesn’t matter where you start, but it matters that you start this journey.”