Taika Waititi has made a name for himself as a director who blends humour with deeply emotional storytelling. Nowhere is this more evident than in Jojo Rabbit (2019) and Boy (2010).

Both films showcase Waititi’s signature style—balancing humour with weighty themes—yet they take vastly different approaches to exploring childhood, imagination and disillusionment.

Taika Waititi, also known as Taika Cohen, is from the Raukokore region on New Zealand’s East Coast. He is the son of Robin Cohen, a teacher, and Taika Waiti, an artist and farmer. His father is Māori (Te Whānau-ā-Apanui), while his mother has Ashkenazi Jewish, Irish, Scottish and English ancestry. This mixed heritage often informs his work, bringing together perspectives shaped by both Indigenous and Western influences.

Jojo Rabbit transforms the grim landscape of Nazi Germany into a satirical playground of misguided hero worship, while Boy roots itself in the raw, small-town struggles of a Māori child’s wish for a father figure. Despite their contrasting settings, both films are similar in their examination of childhood innocence colliding with harsh reality.

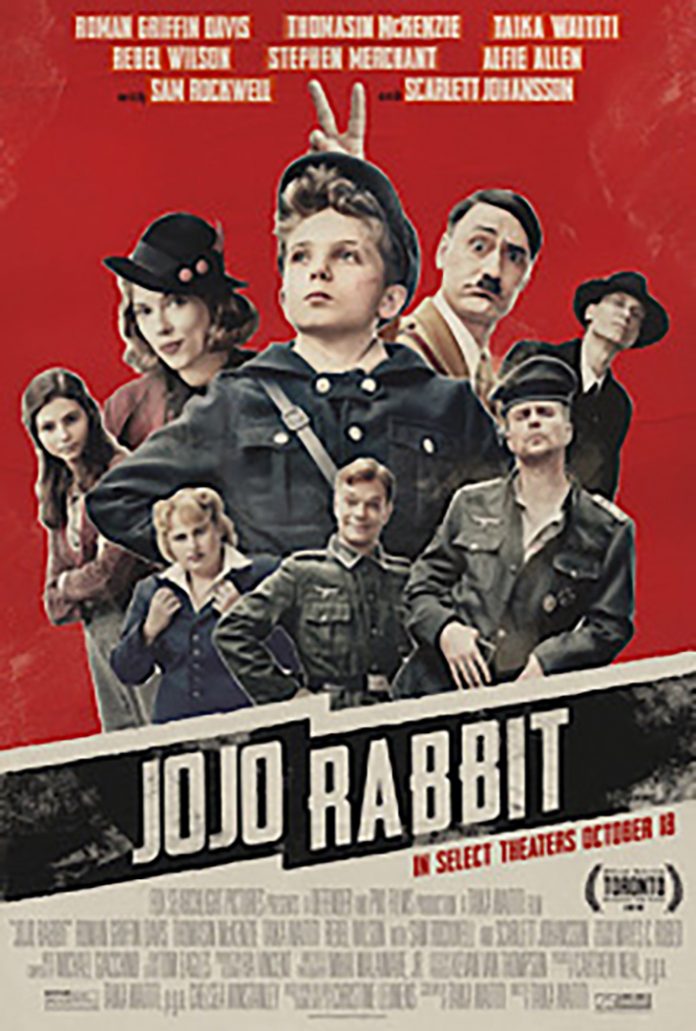

Waititi’s Jojo Rabbit is a bold and unconventional satire that follows Jojo Betzler, a Hitler Youth recruit whose imaginary friend is none other than a clownish version of Adolf Hitler (played by Waititi himself). At its core, the film is a takedown of blind nationalism, seen through the naive eyes of a ten-year-old who has been fed propaganda.

Set during the final days of World War II, Jojo Rabbit captures a moment in history when fascist ideologies were falling apart, yet still held a dangerous grip on the minds of the young and impressionable.

The absurdity of Jojo’s beliefs is gradually broken down when he discovers that his mother is hiding a Jewish girl in their home. The film’s comedic elements—from Waititi’s over-the-top Hitler to Sam Rockwell’s eccentric portrayal of a disillusioned Nazi officer—create a surreal contrast against the dark historical backdrop. However, beneath the humour lies a story about love, loss and the transformative power of empathy, as Jojo learns to see beyond hate and fear.

Meanwhile, Boy offers a quieter, more intimate narrative grounded in Waititi’s own Māori heritage. Set in 1984 rural New Zealand, in an impoverished Māori community, the film follows Boy, an 11-year-old Michael Jackson superfan who has constructed a mythic image of his absent father, Alamein. When Alamein returns, it becomes painfully clear that he is no hero but a drifting ex-con who cares more about finding buried money than raising his children.

Through Boy’s story, Waititi addresses the trauma and systemic challenges faced by Māori communities, including poverty, family separation and the lingering effects of colonization.

Where Jojo Rabbit tackles fantasy and delusion through a political lens, Boy presents it as a deeply personal coming-of-age journey. The film’s humour is gentler, rooted in the awkwardness of childhood rather than outright satire, making its emotional punches hit even harder.

What unites these two films is Waititi’s masterful use of humour to reveal deeper truths. Both protagonists idolize deeply flawed figures—Jojo with Hitler, Boy with his father—only to have their illusions shattered. The difference lies in tone.

Jojo Rabbit is exaggerated and theatrical, forcing audiences to laugh at the absurdity of fascism before reminding them of its horrors. Boy, on the other hand, is tender and melancholic, drawing viewers into a world of scraped knees and broken dreams, where reality doesn’t need embellishment to feel devastating.

Both films are worth watching, but their impact will depend on the viewer.

Jojo Rabbit delivers biting satire wrapped in a coming-of-age war story, ideal for those who appreciate dark humour with a meaningful message. Boy is more subdued but just as affecting, offering a poignant and deeply personal exploration of fatherhood, abandonment and self-discovery.

Both Jojo Rabbit and Boy showcase Waititi’s ability to craft narratives that are as hilarious as they are heartbreaking.

Whether one prefers the surreal escapism of wartime satire or the grounded heartbreak of rural New Zealand, Waititi proves that he is a filmmaker unafraid to tackle serious themes through an unconventional lens.