After over six months of tense negotiations, Ontario’s 24 public colleges narrowly avoided a strike this term.

A Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) signed by the bargaining team representing over 15,000 college faculty brings significant benefit gains for precarious faculty, who make up 75 per cent of the workforce.

Durham College (DC) President Dr. Elaine Popp expressed relief after a potential strike was averted, calling it “a significant win for everyone on our campuses.”

However, unresolved issues have been referred to arbitration, with arbitrator William Kaplan set to rule on the remaining contract items at a later date.

“Faculty working conditions are student learning conditions,” said Ravi Ramkissoonsingh, Chair of the faculty bargaining team, in the release. “With a historic strike mandate and provincewide organizing, faculty sent the clear message that we’re ready to stand up to protect both.”

Despite this resolution, systemic issues persist in Ontario’s post-secondary education system, including chronic underfunding, reliance on precarious employment and misallocation of resources.

“Chronic underfunding is absolutely the single greatest reason that we find ourselves in the situation that we’re in,” said Kathleen Stewart, Chief Steward of Local 354 representing Durham College faculty.

“It would be like me saying to you, ‘Your rent is going up, your groceries are going up, your gas is going up, but you’re not allowed to ask for any money from your parents and you’re not allowed to get a job,’” said Stewart.

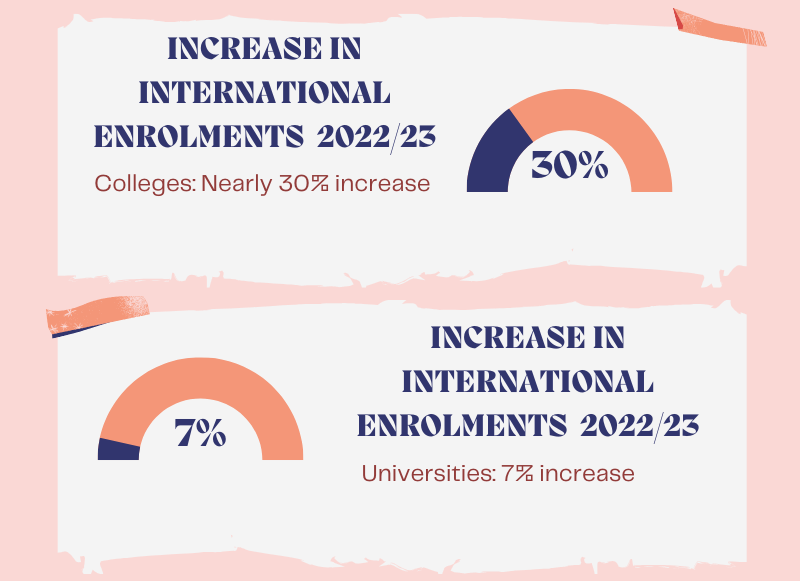

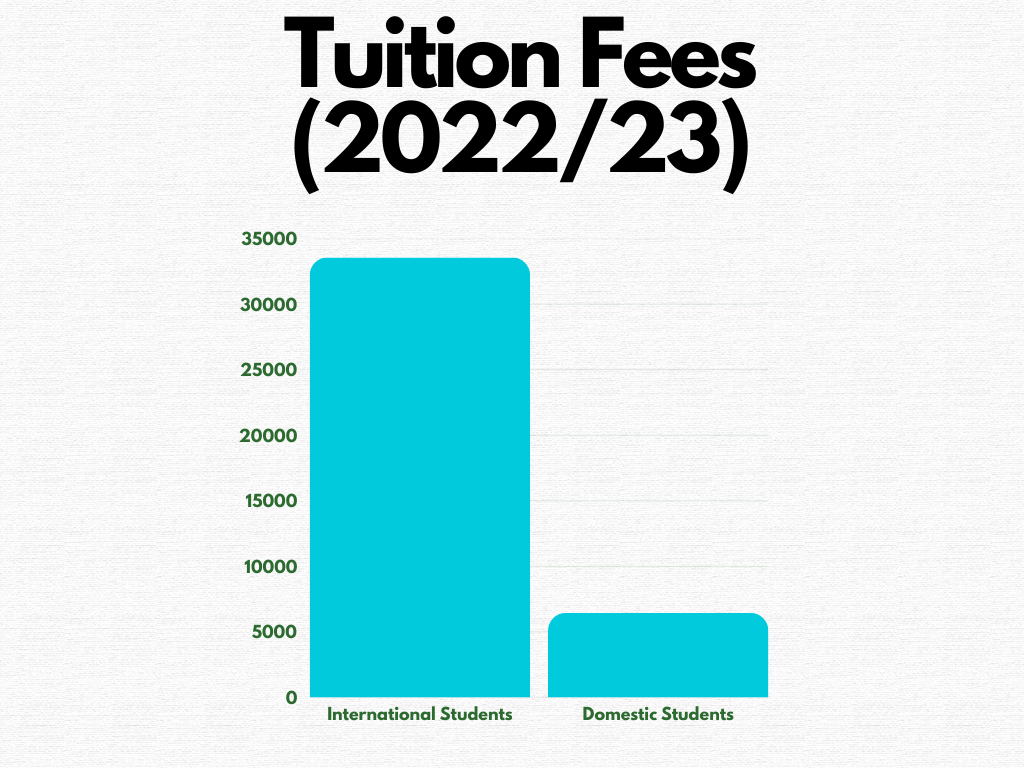

With restrictions on international student visas now in place and frozen domestic tuition fees, colleges are feeling the financial strain.

“For every one international student, I have to find three domestic students to replace that lost income,” said Stewart. “We cannot rely on international students to fund education…

“Education should not be political.”

Popp acknowledged the chronic and long-standing underfunding from the provincial government and the abrupt decline in international student enrolment as key issues impacting the colleges.

“Durham College is not immune to the situation,” Popp said. “Despite this, we remain committed to minimizing the impact on employees and students wherever possible while ensuring DC’s long-term success.”

To address these challenges, DC’s Executive Leadership Team has developed strategies aimed at safeguarding the institution’s financial stability. These include exploring new revenue options, reviewing hiring practices, pausing nonessential renovations and identifying cost-saving measures.

The college is also offering voluntary retirement programs for eligible employees and managing vacation and lieu time for staff.

Popp praised DC employees, saying, “They remain dedicated to supporting each other; they are resilient and focused on student success. Together, I’m confident that we will overcome these difficult circumstances.”

Precarious workers remain a pressing issue, with 75 per cent of Ontario college faculty working part-time or on contract.

“You have people that have to cobble together many jobs in order to try to earn a living,” said Stewart, highlighting the lack of compensation for essential tasks like grading, lesson preparation and student meetings.

“You can’t expect to have the same quality of education if people are coming and going all the time and you have high turnover,” she said.

Stewart mentioned that according to a Task Force report prepared after the 2022 bargaining, conservative estimates revealed every full-time professor in the system donates $24,000 worth of personal time to get the work done.

Geoffrey Coulter, a professor in the broadcasting program at Durham College, has been teaching at the college for ten years while balancing another full-time job.

“I work 40 hours a week at my other job, but I take one day off to focus entirely on my students here,” he said. “It’s a lot to juggle, but being super organized helps.”

There’s a considerable amount of time put into preparing for classes that part-time faculty are not paid for, especially when they have multiple classes with 30+ students.

“Preparing is super important. I spent several hours adapting and updating course materials, and I even came in on my own time before the term started to make sure everything was working—there’s no pay for that,” said Coulter.

Partial load and part-time faculty have limited availability for in-person meetings outside of the classroom.

“I can’t really meet in person with students. But I’m very good at email, and although I am part-time, I try to really avail myself to my students.” Coulter said, “I tell my students at the beginning of the class that I’m only an email away and I try to get back to my students within 24 hours.”

“It’s about priorities. When we’re told there aren’t resources for the classroom, professional development, or staff retention, but we’re paying big bonuses… it just should not be happening,” said Stewart, who stated over $800,000 in bonuses and salary increases were paid to Durham College executives in 2022-2023.

At least one member of the executive leadership team gained a 36 per cent pay raise between 2022-2023 while six people had more than a $40,000 pay increase.

These challenges are compounded by a growing administrative workforce.

“In the past 10 years, we’ve added 1,500 managers and only 500 teachers to the system. That makes no sense to me. Three times as many managers as teachers in an education system?” said Stewart.

“College students are reduced to walking dollar signs for the same reason that 75 per cent of faculty are precarious, working contract-to-contract,” JP Hornick, President of OPSEU/SEFPO said in the release.

Hornick criticized what they referred to as a “corporate model of education,” which diverts tuition fees to administrative salaries and vanity projects while neglecting the quality of education.

“The same government that proudly declares that every $1 invested in post-secondary education has a $1.36 return for Ontarians has put Ontario dead last amongst the provinces for per-student funding,” said Hornick.

Stewart echoed this saying: “We are the lowest-funded province. Our funding has not changed. In over 15 years, like since 2008, 2009.”

The average amount of money that most provinces subsidized students is about $15,000 per student and in Ontario it’s just over $6,000 per student.

“It’s not just illogical, it’s irresponsible—Ford is gambling away Ontario’s future. It’s time we bet on a better future for our colleges—one that’s not rigged against students from the outset,” Hornick said.

Stewarty added that the cracks in the system have only widened in recent years, as evidenced by the pandemic.

“The reality is our system’s been in a lot of trouble for a long time and just like our health care system, the pandemic just let everybody see it.”

To address these systemic issues, the union believes colleges need to start with investing in full-time faculty and classroom resources.

“If you create stability in the system by having more full-time people teaching, that is good for the entire system,” Stewart said. “We’re not corporations. We’re supposed to be delivering education.”