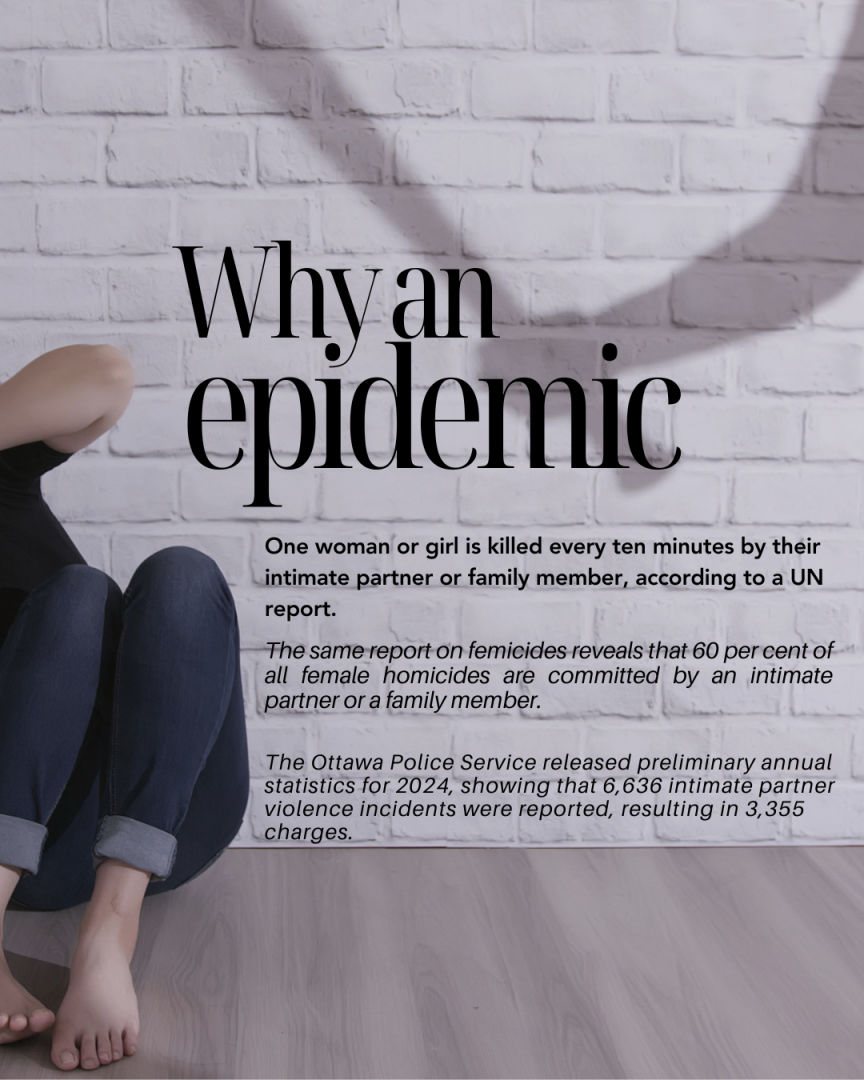

With intimate partner violence (IPV) on the rise and femicide rates climbing, Oshawa has officially declared IPV an epidemic, reinforcing calls for the Ontario government to take action.

The motion, brought forward by Councillor Derek Giberson and seconded by Councillor Bradley Marks in the January council meeting, aligns with the recommendations of the 2022 Renfrew County Inquest. The inquest investigated the tragic murders of three women by their former partner. With unanimous support, the motion was passed.

By declaring IPV an epidemic, Durham Region is taking a significant step in prioritizing resources and advocacy efforts to combat gender-based violence.

Sydney Marcoux, clinical director of Victim Services of Durham Region and a member of the violence prevention coordination council in Durham, played a key role in advancing this motion. She emphasized that the declaration helps direct much-needed funding and attention to the issue.

“By declaring an epidemic, it prioritizes where resources may be put and where advocacy will be needed,” she said.

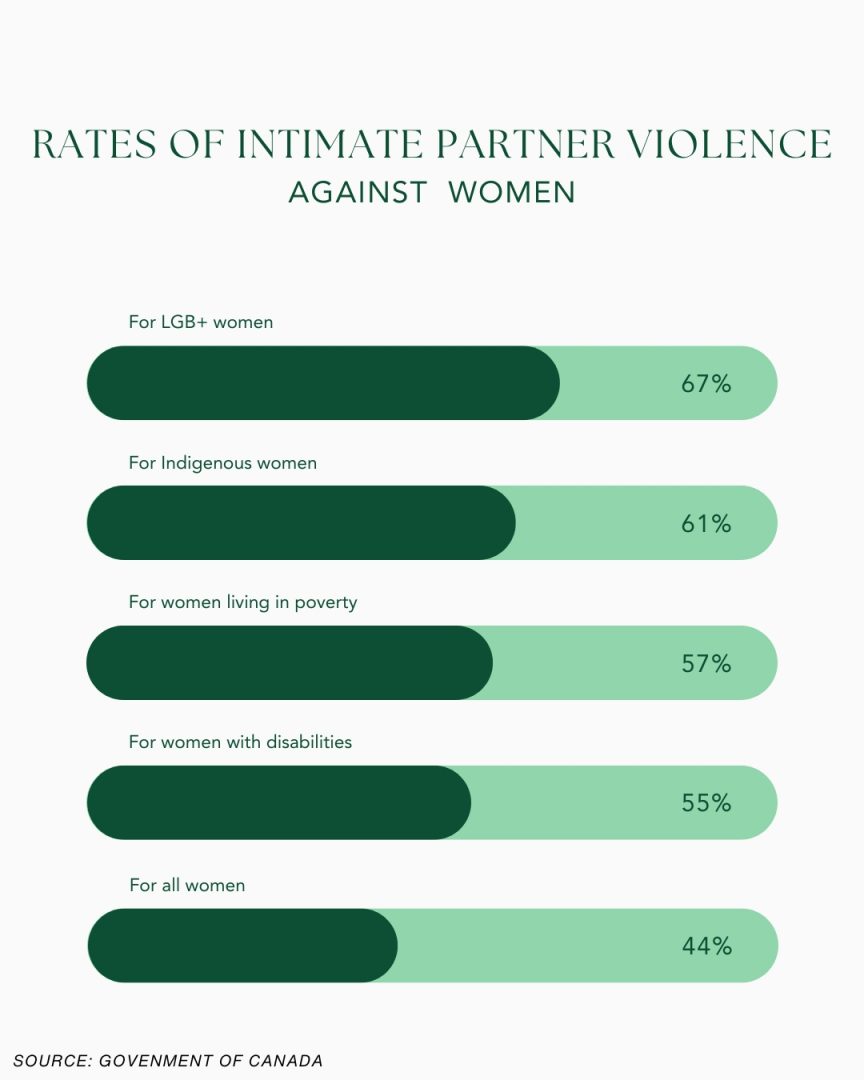

With IPV affecting one in five women in Canada and femicide rates rising, local advocates stress the urgency of increased funding, policy changes and public awareness. Marcoux underscored that this declaration is more than symbolic, it is a necessary step toward systemic change.

IPV encompasses physical, sexual and emotional abuse that occurs in intimate relationships and its devastating impact continues to escalate. In 2024 alone, Ontario saw around 66 femicides—more than one per week—six of which occurred in Durham Region, Marcoux noted.

Victim Services supported nearly 2,600 individuals affected by IPV last year in Durham Region. Despite this growing demand, core funding remains stagnant, particularly affecting their ability to secure safe accommodations for survivors.

“Our numbers are increasing drastically, but our core funding is not, which means that my staff are now under a higher demand to support more people who are being victimized,” Marcoux said.

The funding crisis is a central concern. Councillor Giberson, who introduced the motion, also criticized the chronic underfunding of IPV support organizations, noting that many are forced to “go around with a cap in hand, begging people for money to support them.”

While recognizing the value of community fundraising, he insisted that front line services should not have to rely on donations to survive.

“These are critical services and they should be fully funded by the governments that are responsible for these services,” he said.

Giberson emphasized the significance of municipal governments taking a stand. “It’s important for people who are in leadership to make it clear where their position is on something like this because that influences other decision-makers,” he said.

He also noted that such declarations send a message not only to survivors but also to abusers.

“When you have community leaders who come out very publicly and state their position, for those who are abusers, they may take note of—that society is not viewing what they do as acceptable,” he said.

The motion aligns with broader advocacy efforts urging the provincial government to formally declare IPV an epidemic. “The number one thing is that the provincial legislature declare it to be an epidemic because then that changes the legislative framework that they’ll be working with,” Giberson explained.

While Oshawa’s declaration does not directly translate into additional services or funding, it signals a strong commitment to supporting ongoing advocacy work in Ontario.

Jennifer French, MPP for Oshawa, has long called for the province to take action on IPV. She welcomed the city’s declaration but expressed frustration over the provincial government’s inaction.

“I’m relieved to see that they have finally called for violence against women to be deemed an epidemic, they were the last ones to do it,” French said. “It’s been very frustrating at Queen’s Park, we have called for violence against women to be deemed an epidemic that would allow for different supports and funding at the provincial level (but) the provincial government has refused to do that.”

However, municipal financial constraints remain a significant challenge. “Unfortunately, we’re not in a position financially to provide that core, day-to-day operating funding year to year, which is why I always tell people we need individuals, citizens and organizations to add their voice in asking the province,” Giberson said.

Beyond funding, advocates stress the need for cultural and systemic change in how IPV is understood and addressed. Giberson questioned how society can “denormalize something that for some people is normal,” highlighting the necessity of education and prevention efforts.

Addressing the root causes, he highlighted the complex gender dynamics at play in IPV. He emphasized that while men are the primary perpetrators, many abusers misconstrue their actions as displays of strength.

“Most of the men who are abusers believe they’re acting with strength, but they’re actually acting with weakness,” he said. “So how do we shift that perception around what it means to be a man?”

The momentum for change is building across the province, with approximately 100 Ontario municipalities having declared intimate partner violence an epidemic over the past few years.

While Oshawa’s declaration marks important progress, Giberson acknowledges that meaningful change requires both legislative action and financial support from higher levels of government.

Until then, organizations like Victim Services of Durham Region will continue to provide support with the resources they have, while leaders like Giberson and Marcoux push for systemic change.

As Giberson put it, “We can do the best that we can, but at the end of the day, we don’t even have the resources available in our hands to be able to do that.”